The best and worst aspect of web development is that approaches change reasonably often, and sometimes even for the better! I’m catching up on some of these trends:

- Hybrid rendering: Blurring the lines between client and server with SSR and hydrated state

- Identity as a service: Handling authentication and authorisation through third party delegation

- Serverless: Isolated (often stateless) compute on managed infrastructure with great scalability promises

- Live views: Applications subscribe to data updates rather than waiting for page refreshes

- GraphQL: Strongly typed APIs with smart servers and clients

They all deserve their own posts. This is an attempt to highlight the interplay between these topics, with a focus on integration and security rather than implementation. I’ll be looking specifically at a pretty powerful combo for modern collaborative web applications: NextJS with Apollo Client, Hasura GraphQL, and Auth0.

At the end of this post, you’ll hopefully have a better understanding about some strengths and weaknesses of a “hybrid” approach to rendering views with authenticated data in this particular stack. The specifics described here loosely follow a Hasura + NextJS tutorial.

Disclaimer: I have not operated this architecture in production (yet!), but learned enough to provide a “top-down” view of the moving parts.

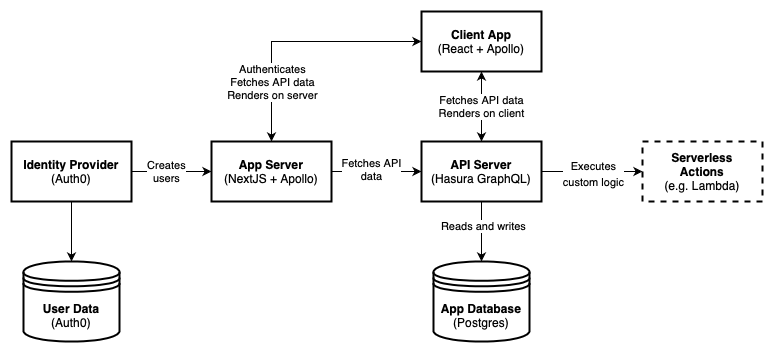

Components

- Client Application: Uses Apollo Client for fetching GraphQL data in the browser, and client-side rendering via NextJS/React and Apollo Client

- App Server: Uses a set of serverless functions orchestrated by NextJS. Handles server-side rendering (SSR) also via NextJS/React and Apollo Client

- API Server: Uses Hasura, a GraphQL API server handling authorisation, but not authentication.

- App Database: Uses a standard Postgres instance, with a schema managed and queried by Hasura

- Identity Provider: Uses Auth0, an Identity-as-a-Service provider.

- User Data: Auth0 has its own identity store, where you can access user metadata that’s not specific to your app

GraphQL live views in Hasura

Hasura “wraps around” a standard relational database schema, and has a refreshing approach to keeping business logic out of this layer: The 3-factor app architecture. In short, the API layer provides the boilerplate for CRUD and authorisation, and can be extended via custom resolvers running in serverless functions elsewhere. Instead of providing a broad execution environment or web framework, it enables reliable event streams which can also be responded to by separately hosted serverless functions.

As an example, a restaurant booking would have roughly the following asynchronous flow:

- The client sends a GraphQL mutation with the booking request to Hasura

- The client subscribes to updates on this pending booking request object via GraphQL subscriptions (at some point later)

- Hasura emits event on new booking request record creation

- Event gets picked up by a serverless function which interacts with a third party booking engine

- The result of this custom business logic process is written back to the Hasura-monitored database

- The client receives an update with the new state (e.g. subscription confirmed)

Serverless isn’t a mandatory feature, but having a “one function per event type” constraint keeps the business logic small and cohesive. And if your serverless functions don’t rely on other more constrained resources (such as writing back to the Hasura-managed database), they’ll scale really well!

While this architecture looks close to traditional queue-based systems, there’s a certain simplicity in using the database as a queue rather than a separate component. There are lots of traps in relational database queues, and Hasura only provides guarantees for “at least-once” and “out of order” delivery of messages. I haven’t used this system in production, but the overall adoption rates of Hasura makes me hopeful that they’ve solved this well for transactional use cases.

Hybrid rendering in NextJS

NextJS is a Javascript-based web framework built on top of React. By virtue of using Javascript both on the server (NodeJS) and in the browser, it blends the boundaries between where data can be fetched and rendered.

For “static” content (same for every viewer), it can pre-render pages at build time, or in a classic per-request server process. While it can render into static HTML, serving pre-rendered views through its serverless functions allows some neat tricks around incremental regeneration.

For “dynamic” content (e.g. authenticated or otherwise personalised views), pre-rendering usually isn’t practical. You can use NextJS as a traditional web framework, with per-request server rendering. Or you can use it as a static provider of files creating a Single Page App that handles data fetching and rendering on the client. Or … you can do both!

Rendering GraphQL data on the server and client with Apollo

Apollo Client can consume GraphQL data in both a server and client context. It’s somewhat framework agnostic, but has great integration to provide this data to React components. Unlike a standard HTTP client, it leverages the GraphQL schema to build up a smart cache. In an interactive browser context, this smart cache can be used for optimistic mutation results, updating your view before the server has even processed the state change. But it also makes it smart enough to know which queries have already been run, and can be retrieved from memory while the real query is still retrieving (potentially new) data in the background.

Apollo can introspect a React component tree to identify its data requirements expressed in GraphQL queries and fragments (via getDataFromTree()). With this knowledge, it can retrieve all data required for a given view on the server. NextJS kicks off this process via a custom getInitialProps() implementation and takes care of the rendering.

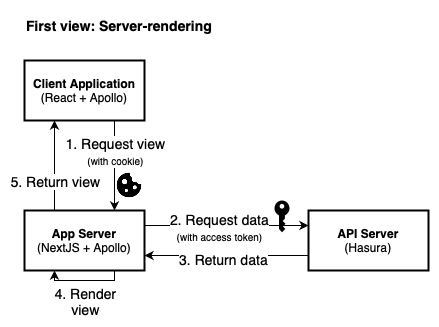

To recap, here’s the initial rendering process:

- Client requests initial view from NextJS

- NextJS triggers Apollo to fetch all required data via GraphQL

- Apollo introspects the component tree for data requirements, and executes queries

- NextJS renders the view based on the returned data

This is where it gets interesting: The data retrieved by Apollo on the server is serialiseable. It gets passed to the client, which can rehydrate it and avoid running the same queries again.

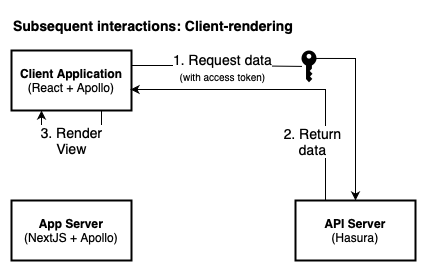

Live views via websockets with Apollo

Live views “bind” to remote data updates, which is especially useful in collaborative multi-user contexts. While the GraphQL client (Apollo) acts as a standard HTTP client on the server, in the Hasura approach it gets initialised as a websocket client in the browser. This setup allows subscriptions to GraphQL data, an essential component of the 3-factor app architecture.

Continuing from the intial rendering process above, here’s what it might look like to get updated data which are collaboratively edited by other users:

- Server-rendered view is displayed, initial Apollo cache is rehydrated

- A new subscription for some of the viewed data is established via websockets

- Another user or async process triggers a change to the viewed data

- The subscription receives new data

- Apollo updates its internal cache, and triggers re-render on any components relying on this query/subscription

For simplicity, websockets are also used for “standard” GraphQL operations (queries and mutations) that could be performed via a HTTP client.

Authentication via Auth0

Auth0 is a flexible identity-as-a-service provider, and handles the hard bits of securing user information and authentication flows. Most importantly for developers, it provides SDKs for every conceivable authentication flow. Since we’re buliding an (initially) server-rendered web application, we’re focusing on OAuth2 for API authorisation tokens and OpenID Connect (OIDC) for login tokens.

In the case of Hasura, the recommended integration creates or updates “shadow” user records in the Hasura-managed database on every login request to Auth0. These user records will point to a unique identifier assigned by Auth0.

When Auth0 is asked to issue a token (e.g. through a login action), additional metadata can be added to the token identifying the user as well as their role in this application context. Most commonly this is implemented through JWT claims in an OAuth2 or OIDC flow. Since this information is contained in a signed JWT where only Auth0 holds the private key, it can be verified with Auth0’s public certificates within the API (Hasura). This kind of cryptography is essential to the delegation model between different services, especially when they involve untrusted channels and devices.

There are flows for Single Page Applications that don’t require a server environment to login and receive an access token that can be used for API access. This can be accomplished through auth0.js without any knowledge of NextJS. Apart from the complexity of securing this process in untrusted environments, it would also negate a main driver to fully utilise NextJS: Performing the initial render on the server, which would require authenticated requests to the API.

A server-based authentication flow and render process looks like this:

- Browser requests authenticated resource from NextJS (e.g. a page)

- NextJS determines that a login is required, and initiates an OAuth2 flow (asking for hybrid code/id grants)

- The browser request gets redirected to the Auth0-hosted login screen

- After login, Auth0 invokes the defined server-side callback in the app with a

codeandid_token - NextJS calls Auth0 to exchange the

codefor anaccess_token - NextJS encrypts the resulting information in a session cookie

- NextJS provides the (signed) access token to the browser, where it gets added to localStorage

There’s a great Auth0 blog post about authenticated NextJS to dig through more details.

API access via a mix of session cookies and JWT state

Did you notice that the access token is stored in two places as part of the authentication flow?

- Session cookie: Because of the stateless nature of serverless, there is often no shared session backend. Sending (limited) session information through an encyrpted cookie keeps the architecture simple. In our case, the cookie contains the access and id tokens, and is used for server-side rendering.

- Browser localStorage: For client-side rendering, the access token needs to be accessible to Javascript in order to form an authenticated request to a third party API (outside of the session cookie domain).

Compared to secured cookies, storing access tokens in the browser increases the security surface through Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) and Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF). This requires additional care in how the application is built. A safer alternative approach is to proxy API requests through the origin server with session cookies.

Conclusion

There are a lot of moving parts here compared to a traditional “monolithic” approach of many web applications. It’s an incredibly versatile approach, but also introduces many failure modes that simply don’t exist in applications where most of these workloads happen in-memory rather than over the network.

I’ve really enjoyed working through the details here. Not having operated this architecture in production, its too early to form an opinion, but I have some initial impressions:

- Hybrid rendering: Rendering Javascript on both the server and the client is pretty neat, and can really improve the user experience (Headless CMS, anyone?). For processing authenticated views, I’m unconvinced that the added complexity is worth the payoff. While server-managed authentication is easier to secure, it puts a lot of responsibility back on the developer to understand the context they’re acting in (server vs. client). There are scenarios where secrets mistakenly get added to client-side state, or where authenticated views get over-cached and shown to the wrong viewers. At least in this particular stack, authenticated hybrid rendering still feels pretty rough, which is illustrated by the amount of complex boilerplate code required.

- Identity-as-a-service: I’ve maintained and secured custom authentication and authorisation logic in Silverstripe CMS for many years, including handling the security friction that inevitably arises. Hence I’m a big fan of dedicated services to help teams focus on building their actual features.

- 3-factor app architecture: I’ve spent a lot of time inventing (and re-inventing) a GraphQL module for Silverstripe CMS as part of a group of open source maintainers (well, mainly @unclecheese). Mapping database schemas to an ORM and then scaffolding it into coherent GraphQL types is hard. Especially if you want to reduce boilerplate and keep it performant. Hasura and the architecture it promotes are an intriguing take on decoupling business logic from an API layer that’s extremely fast to build with.

- Live views: Collaboration features are becoming table stakes for many applications on the web. Even the humble personal todo list attracts “share edit access” features. It can be tough to retrofit a subscription-based architecture into an existing app (again, talking from experience with Silverstripe CMS…). Live views are the way forward, and both client and server stacks for non-trivial apps need to start accommodating them.